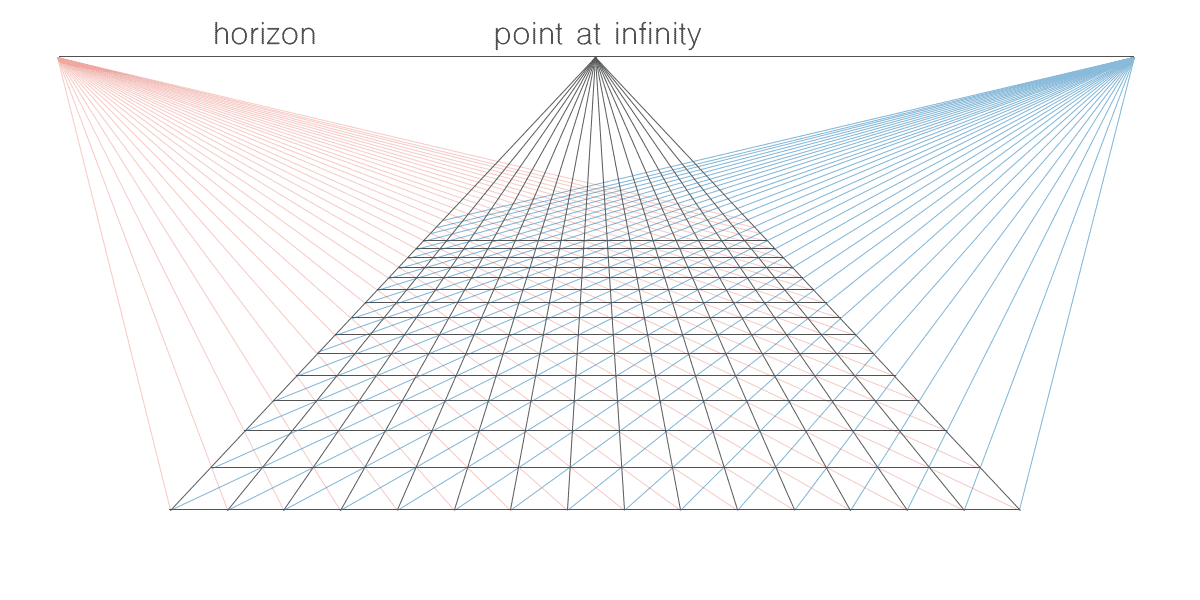

In Euclidean geometry, two lines are said to be parallel if they lie in the same plane and never meet. Moreover, properties like this one don’t change when a Euclidean transformation is applied (translation/rotation). However, what we perceive in real life is different from what’s described by Euclidean geometry.

This problem coincided with the one Renaissance artists had while trying to paint on a canvas. When they tried to paint tiles on a canvas, they realized that the following rules applied:

- parallel lines meet on the horizon

- straight lines must be represented on the page by straight lines

- the image of a conic is also a conic (for example a circle is drawn as an ellipse depending on the perspective)

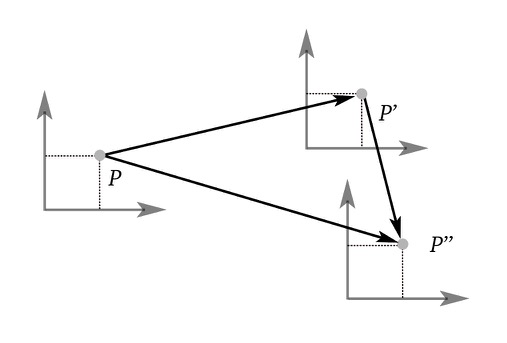

projection

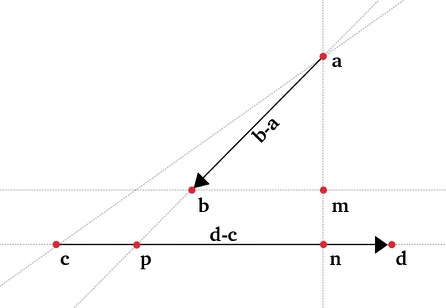

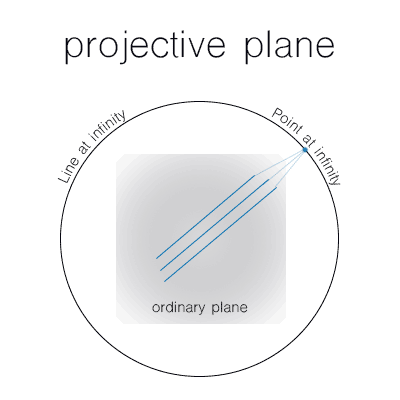

The French mathematician Girard Desargues , researching more on this new type of geometry, had the necessity to have a point at infinity. He introduced the concept of a line at infinity, which helped define the point at infinity as follows:

For every family of parallel lines on some ordinary plane, there’s one point at infinity where they all meet, which lies on the line at infinity

projective plane

An ordinary plane plus the line at infinity is called a projective plane

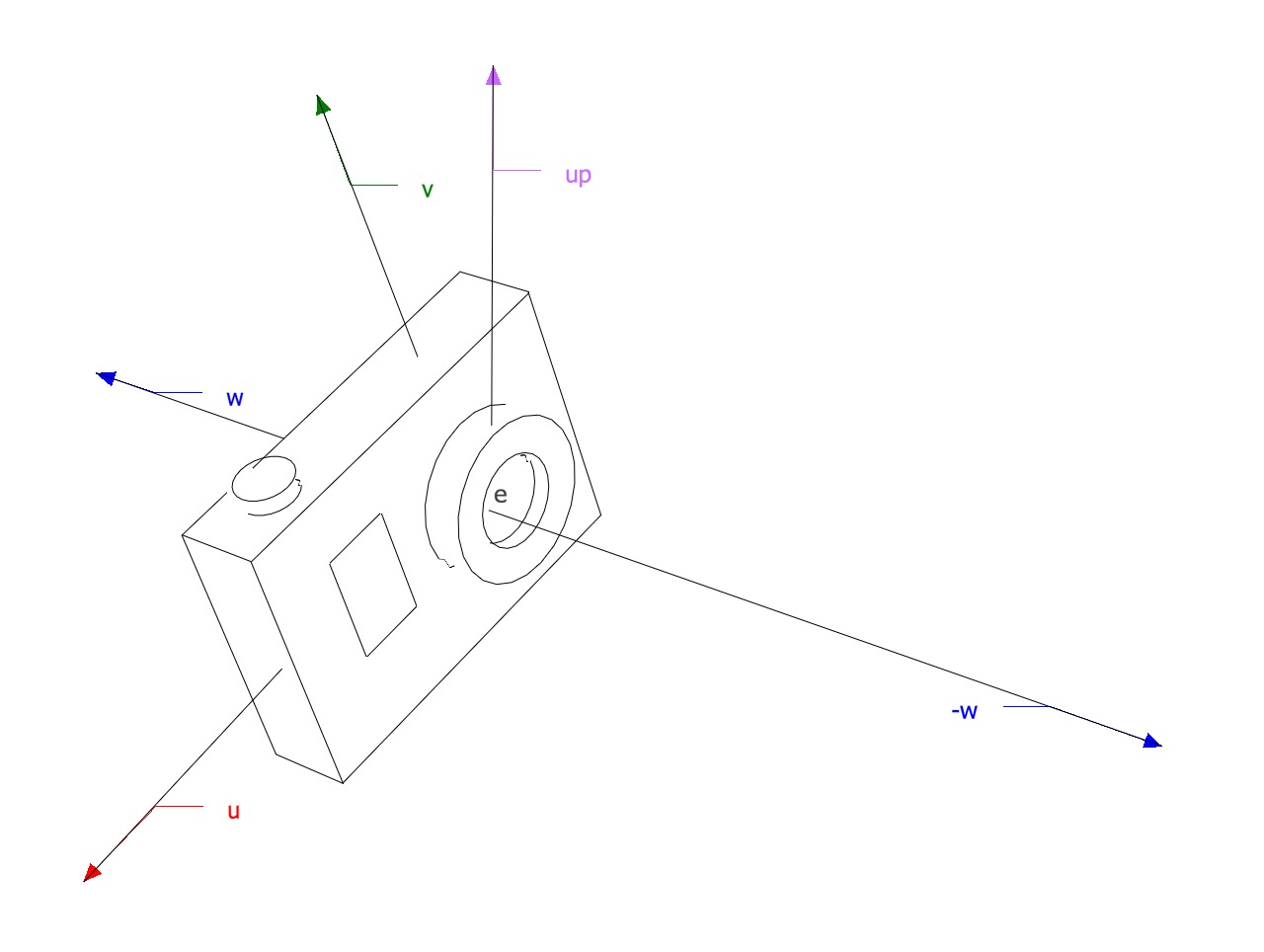

Projective geometry exists in any number of dimensions (just like Euclidean geometry). When we take a picture using a camera, the imaging process makes a projection from

Properties of projective transformations:

- Preservation of type (points remain points, and lines remain lines).

- Incidence (a point remains on a line after transformation).

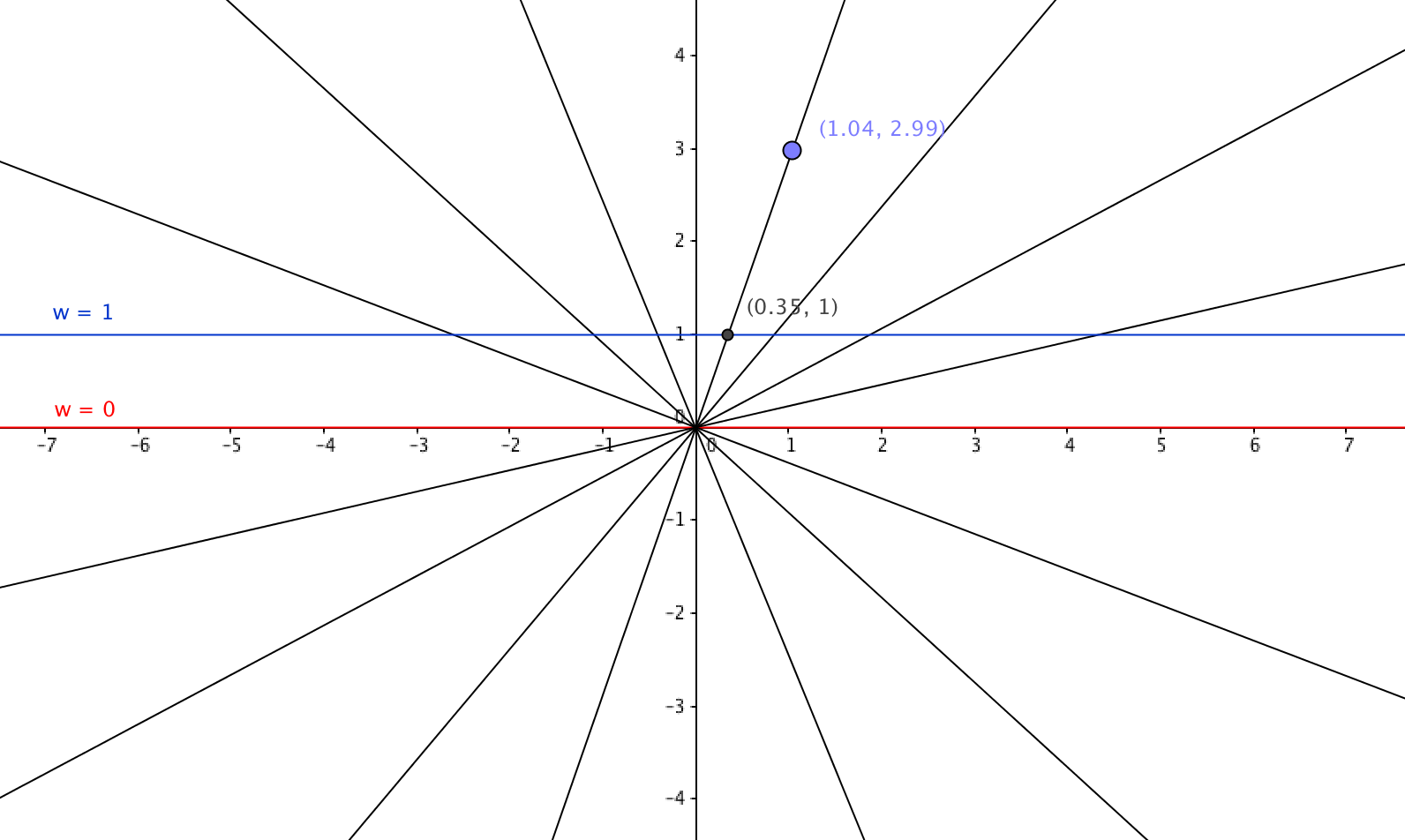

In 1D, there’s the projective line, which is an ordinary line plus one point at infinity that can be reached by moving towards each end of the line.

Projective line

Spaces of 1-dimensional subspaces that exist in 2-dimensions, i.e., any line that passes through the origin in a 2-dimensional space.

Let

Any 1D point is represented in projective geometry as the pair

projective line

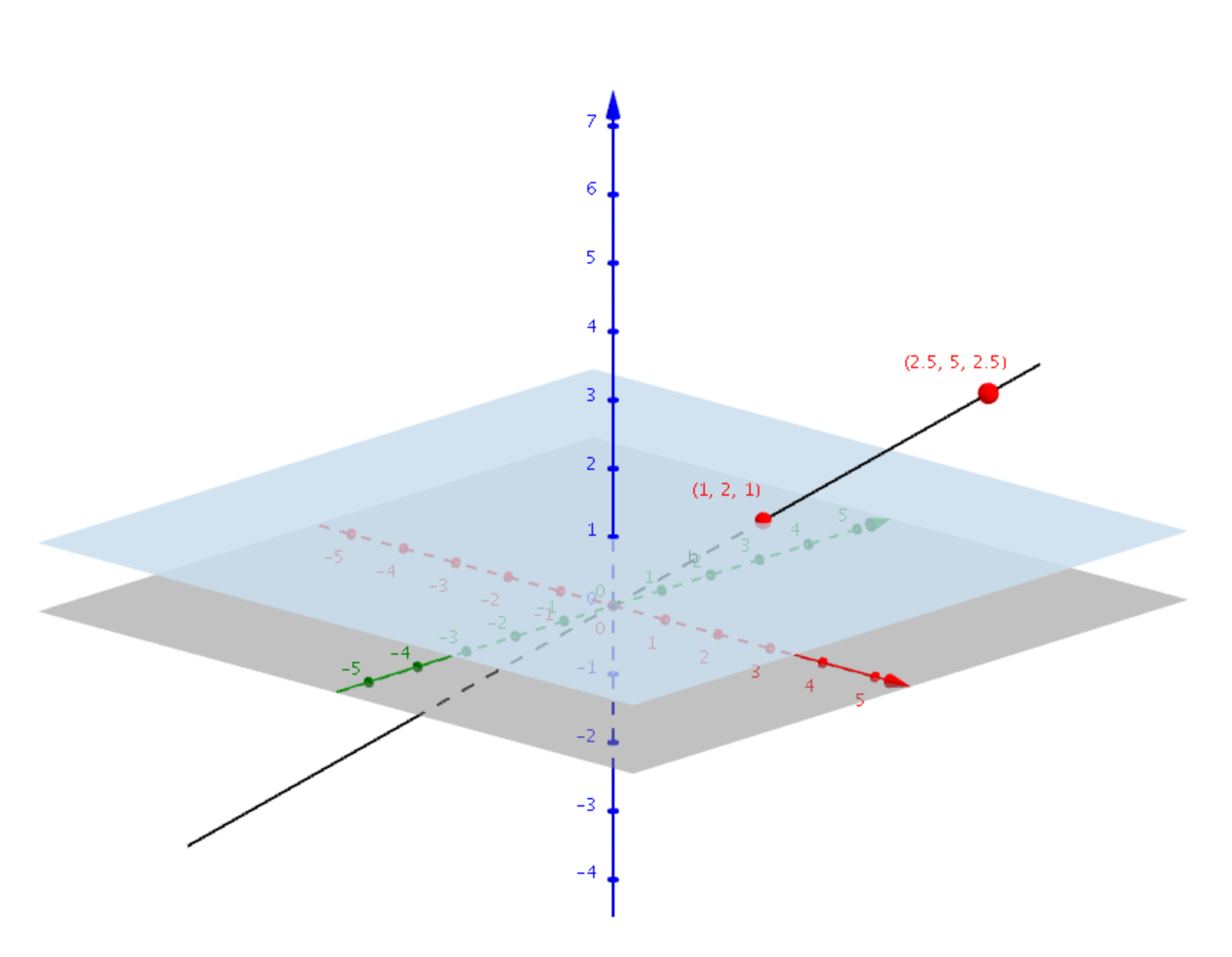

Projective plane

Spaces of 1-dimensional subspaces that exist in 3-dimensions, i.e., any line that passes through the origin in a 3-dimensional space.

A similar situation is seen in a 3-dimensional space. In this space, any line that passes through the origin intercepts the plane

Any 2D point is represented in this space as the triplet

projective plane